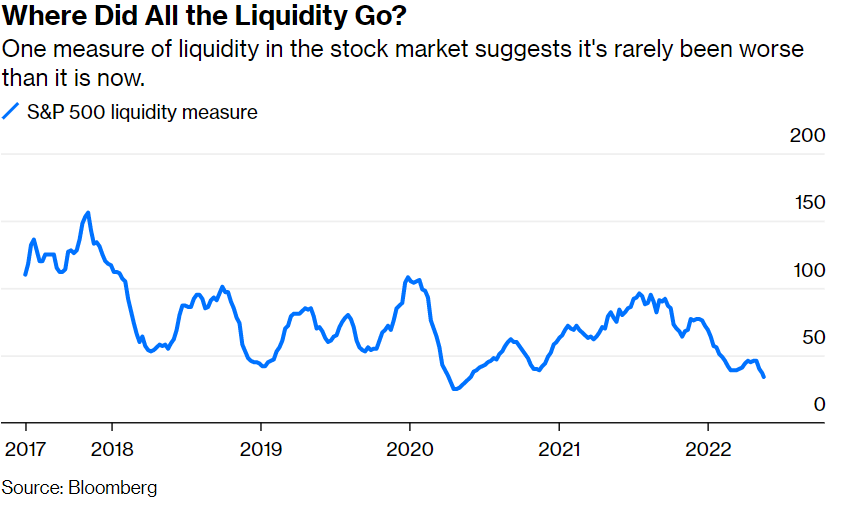

Recent Bloomberg article reveals the next challenge to hit markets – liquidity or the lack thereof. While the US is recognized for having one of the most liquid markets, liquidity has slowly been drying up in the markets. One of many reasons is attributed to the Federal Reserve tightening monetary conditions by raising interest rates and shrinking its massive $9 trillion balance sheet. Don’t forget, the Fed had been pumping $120 billion per month directly into the financial system since the early days of the pandemic by purchasing bonds in the open market. Now, that money will be coming out. This has contributed to higher levels of volatility, which has an inverse relationship to liquidity. And in the futures markets, margin requirements can also impact liquidity. As they increase, it reduces the number of contracts an investor can trade without posting additional margin. As Bloomberg News’s Cameron Crise pointed out last week, stock market liquidity is the worst ever outside the financial crisis and early Covid.

The market for U.S. Treasury securities, called the most important in the world, is also seeing a reduction in liquidity. So much so that it is not unusual to see rapid and wide swings in yields for no apparent reasons. The Fed said in its report that “liquidity metrics, such as market depth, suggest a notable deterioration in Treasury market liquidity.”

“Tick” size also contributes to liquidity shortfalls. A tick is the smallest increment that stocks, futures, or bonds can trade. One tick in the stock market is one penny. Also, if the spread between the bid and offer is too small, that also reduces incentives to display liquidity, or post bids and offers. I have been a proponent of rolling back decimalization in the stock market and going back to fractions, which would increase incentives for market makers to post bids and offers. Years ago, the Securities and Exchange Commission conducted a study with small cap stocks to determine the effects on liquidity of varying tick sizes. Although the results were inconclusive, the agency should have included large, liquid stocks to get an informative outcome.

Most outside observers look at bid-offer spreads linearly, thinking that the wider they are, the more costly to investors. Yes, they may hurt the individual who buys 100 shares of General Electric Co. in his or her E-Trade account, but individuals are also investors in mutual funds and such, which transact in very large size and would benefit from the additional liquidity created by larger tick increments. In stock index futures, tick sizes are extremely small, with the Nasdaq 100 futures trading in quarter ticks even as the index vaulted over 10,000. This benefits practically no one, except for high-frequency traders. Interestingly, high-frequency traders are the biggest, most profitable customers for the exchanges, and businesses typically want to take care of their biggest, most profitable customers. Doing something as simple as increasing tick size would harm high-frequency traders but increase market quality and depth.

Some people would prefer to see liquidity decline so that it becomes harder and more costly to trade, giving investors more incentive to buy an asset and hold it for the long term. I look at it a different way in that if an asset is easy to trade, it increases its attractiveness, and therefore its valuation. The lack of liquidity is a very complex problem that comes down how the exchanges are compensated, which is in the form of small fees on a per-share or per-contract basis. More volume equals more fees which equals more profit. I would hope that exchange officials are working to figure out how to solve this problem. The answer is simple: increase incentives for posting liquidity, and tick size is a small part of that. As bad as liquidity is, it is possible for it to get worse.