Fresh evidence of accelerating inflation rattled bond markets anew on Wednesday, sparking large swings in Treasury yields as traders shifted their bets on how the Federal Reserve and the economy might respond.

Treasury yields, which rise when bond prices fall, jumped immediately after the government released new consumer-price index data, which showed broad-based inflation reaching another four-decade high.

Yields on longer-term Treasurys, however, quickly gave up those gains, reflecting the complex crosscurrents that have led to increased volatility in recent weeks. Major stock indexes fell, reflecting a growing belief among investors that the Fed will do whatever it takes to slow inflation, including pushing the economy into a recession.

As highlighted by Wednesday’s report, sky-high inflation remains a major concern for investors. At the same time, other measures of inflation haven’t been as elevated as CPI data. Investors have also focused on mounting signs of slowing economic growth over the past month, causing many to bet that faster rate increases from the Fed now would just lead more quickly to a recession and future rate cuts. That in turn has boosted longer-term Treasurys.

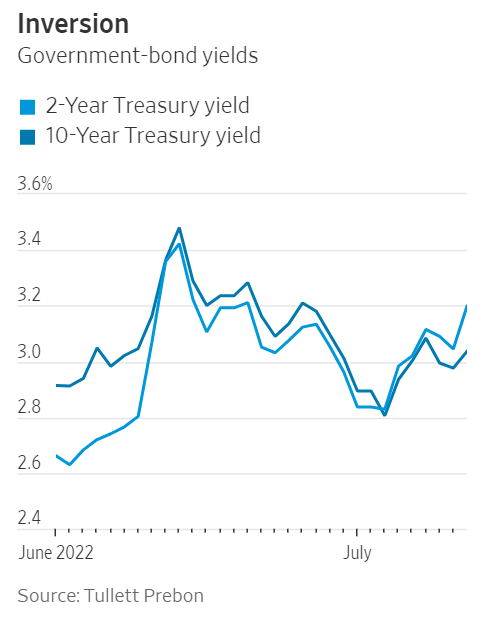

The yield on the benchmark 10-year U.S. Treasury note settled at 2.904%, down from as high as 3.069% right after the CPI report and 2.958% Tuesday, according to Tradeweb.

The two-year yield, which is more sensitive to near-term Fed policy, held gains on the day, closing at 3.142%, compared with 3.043% Tuesday.

Competing concerns about inflation and slowing growth have pushed the 10-year yield to nearly 3.5% and as low as roughly 2.8% since mid-June—a wide range that marks a departure from earlier in the year when yields marched steadily upward.

Heading into Wednesday, traders were particularly concerned about so-called core inflation, which excludes volatile food and energy categories. As it turns out, that gauge jumped 0.7% in June from the previous month—above the 0.5% increase forecast by economists surveyed by The Wall Street Journal.

“The main take is that it’s definitely bad news for the Fed,” said Jan Nevruzi, U.S. rates strategist at NatWest Markets. “The inflationary pressures are still there.”

Traders quickly ramped up bets that Fed officials will raise rates more aggressively at their meeting later this month. Some now think the Fed will lift rates by a full percentage point, a move that few had thought likely earlier this week. Futures markets were pricing in a 79% chance of that by Wednesday afternoon, up from 8% on Tuesday, according to CME Group’s tracker.

“We expect the conversations regarding a 100-basis-point hike to pick up in earnest,” BMO Capital Markets analyst Ian Lyngen wrote in a research note.

Bets on a larger rate increase pushed the two-year yield further above the 10-year yield, a situation known as an inverted yield curve, which has often predicted an approaching recession. Treasury yields largely reflect investors’ expectations for what short-term interest rates will be over the life of a bond. So when longer-term yields fall below short-term yields, it suggests investors are expecting future rate cuts from the Fed due to a struggling economy.

The two-year yield finished 0.238 percentage point above the 10-year yield Wednesday, the largest gap in that direction since September 2000, according to Dow Jones Market Data.

Largely dictated by projected Fed policy, Treasury yields themselves set a floor on interest rates across the economy, with rising yields this year leading to sharply higher borrowing costs for both households and businesses. Higher Treasury yields have also hurt riskier assets such as stocks by offering investors a more attractive return on what is essentially a risk-free investment if held to maturity.

Wednesday’s sharp reversal in longer-term yields echoed what happened a month ago, when CPI data for May also beat expectations. Treasury yields surged after that report, with the 10-year yield coming close to 3.5% over the next couple of trading sessions. Yields, though, then started sliding, as investors bet that higher interest rates would slow growth and responded to a series of economic reports that appeared to back up that thesis.

The Fed, which targets 2% annual inflation, uses a different gauge, the Commerce Department’s personal-consumption expenditures price index, as its preferred inflation measure. CPI typically runs a little higher than the PCE, which is released later each month. But the gap between the two is unusually wide now, partly due to higher energy and housing costs, which make up a larger share of the CPI index.

In data released last month, core monthly PCE inflation for May clocked in at 0.3%, while core CPI prices rose 0.6%.

So far this month, crude-oil prices have declined back under $100 a barrel, down from peaks above $120 a barrel in June. Energy prices have been a central driver of the headline CPI inflation rate, rising 7.5% in June from the previous month.

Recent data have also pointed to slowing wage growth, which some economists say could lead to lower inflation over the medium to long term.