![]() Demand for green bonds and other ethical investment securities is raising the prospect of the market developing a premium over conventional debt.

Demand for green bonds and other ethical investment securities is raising the prospect of the market developing a premium over conventional debt.

Source: Financial Times

Growing demand for ethical investment securities such as green bonds is raising the prospect of the market developing a premium over conventional debt.

As volumes of environmentally friendly and socially responsible finance-raising grow rapidly, the increasing depth of the market could result in the emergence of a premium in prices and lower yields for such paper.

That would enable issuers to charge more for ethically labelled bonds, while investors, operating under mandates to own such debt, face a quandary of having to pay up for new deals.

Lee Cumbes, head of public sector debt Emea at Barclays, has worked on a series of green and social bond deals. He says that pricing has recently begun to look tighter than non-ethically labelled bonds.

“There are signs in the last couple of months that a pricing advantage is beginning to emerge for green bonds,” he says. “Investor demand has really hit us at the back end of this year and that is what’s driving pricing.”

There is some data to back this up: environmentally labelled securities’ total returns have outperformed the global bond average in the year to date, according to ICE/BAML indices.

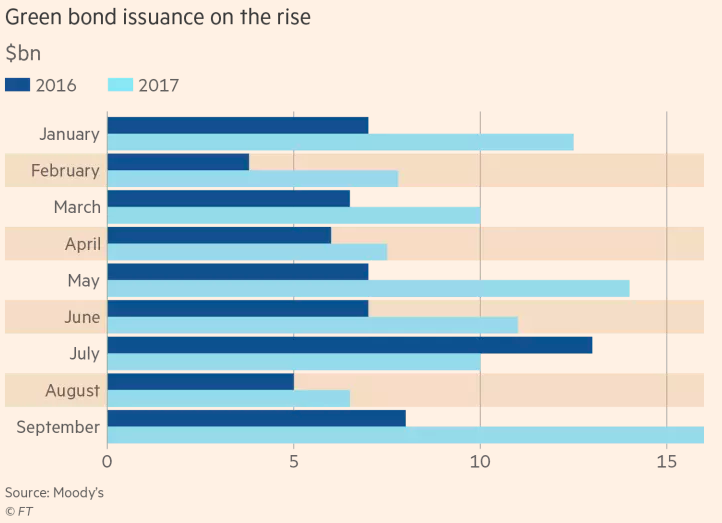

Despite a notable rise in supply this year, the scale of buying interest continues to outweigh it.

Issuance volumes in the decade-old green bond industry are running at a record high, with $95bn sold so far this year according to Moody’s. Last month Fiji became the first emerging market sovereign to issue a green bond, raising $50m in a local currency-denominated issue at five-year and 13-year maturities.

The number of bonds earmarked for broader social purposes is also growing rapidly, although it is a much smaller and newer market. So far this year issuers have raised $7.3bn in syndicated social bonds according to data provider Dealogic, up from $2.2bn in the whole of 2016. Meanwhile, investors have also bought $8.4bn of bonds labelled “sustainable”, up from $6.2bn last year.

For all the jump in issuance volume, this type of labelling is still a drop in the ocean compared to the massive heft of the mainstream bond market. According to Moody’s analyst Matthew Kuchtyak, the biggest factor constraining ethical securities to their specialist niche is the lack of “material pricing benefits”.

A recent Moody’s poll found 40 per cent of bond market participants said this lack of a premium for green bond issuers was holding back the market for ethically labelled municipal debt, for example.

Another factor in the shortage of supply is the time it takes for new issuers to enter the market. “Issuers are being conscientious not to take risks around reporting requirements — there are big reputational risks around debut deals — and that means it takes time,” says Mr Cumbes.

This shortage of supply means ethically labelled bonds do not trade often, says Robert Scharfe, chief executive of the Luxembourg Stock Exchange, which last year launched a green bond exchange to create more transparency for investors.

The exchange now lists 50 per cent of all outstanding green-labelled securities.

Mr Scharfe says that in at least a couple of cases he has seen new issues achieving a clear premium over conventional bonds from the same issuer, while premia are “very common post-issuance” among the relatively small number of trades taking place in the secondary market.

A larger ethical finance market would reduce or eliminate this scarcity premium, he suggests: “A higher volume of issuance would create more trading volume. More liquidity would eliminate the premium in the secondary market which is due to the lack of trading opportunities.”

But even if issuers’ activity increases to match investor demand, ethical paper could still justify a premium due to the additional workload it imposes. Those buying green and social instruments want to know upfront what the money will be used for and it is increasingly common to expect evidence of what it has delivered over time. This can present a costly hassle for issuers.

Spain’s Instituto de Crédito Oficial has been an early issuer in the social bond market. Rodrigo Robledo, its head of capital markets, says issuers “do have some work to do” to demonstrate what outcomes the finance has delivered, which “does add a cost but the benefits mean it makes sense to do it”.

This information is valuable for investors according to Patrick Drum, who manages a sustainable bond fund for Saturna Capital. “As a bond manager I am thinking about resiliency; a premium rewards businesses for making a level of disclosure that you do not usually get in the bond market.”

Some people remain sceptical about the prospect of a “greenium”, though; Rhys Petheram, who co-manages Jupiter Asset Management’s global ecology diversified fund, says there could be “a lot of resistance” from investors.

Managers of environmental, social and green funds have “spent decades trying to convince trustees that they could fulfil their fiduciary duties while still delivering returns”, he says, in a bid to persuade pension funds and other sources of finance that imposing ethical criteria on their investments need not hamper performance.

Paying a premium for ethically labelled paper would undermine all that.