![]() European Commission to launch public consultation on ways to improve market functioning

European Commission to launch public consultation on ways to improve market functioning

Source: The Wall Street Journal

The European Commission wants answers to an intriguing question: Why is it becoming harder for people to trade corporate bonds, even though companies are issuing more of them?

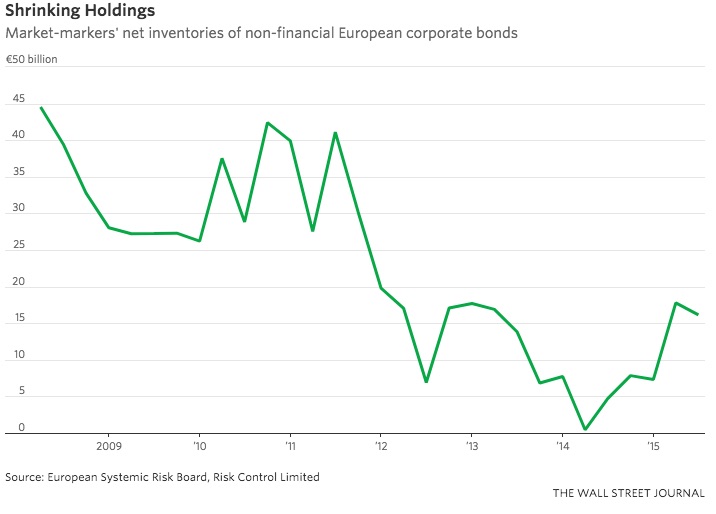

The commission—the executive arm of the European Union—plans to launch a public consultation in early 2018 on ways to improve how the corporate bond market functions. Since the financial crisis, banks and investors have complained about deteriorating trading conditions in corporate debt markets, making it harder to buy and sell bonds in large sizes. Most analysts say that is because banks now hold fewer bonds as a result of the regulation that followed the financial crisis.

Brussels isn’t alone in its concern. The Federal Reserve Bank of New York and the Bank of England have also examined the bond market amid worries that declining liquidity could make it harder for big funds to sell positions in a downturn and trigger a self-reinforcing wave of fire sales.

Here are some charts that lay out the state of Europe’s corporate bond market, based on a study for the commission by consultants Risk Control Limited.

The commission will gather views from what it describes as a broad audience and will follow up on some of the 22 recommendations from a report published this week by a group of industry participants including banks, asset managers and European corporations. Those recommendations ranged from changes to banks’ capital requirements to amending the process around how companies raise money in bond markets.

As the European corporate debt market has grown, the amount of bonds that trade regularly has declined by around 10 percentage points.

“The question is what would happen now if we go into another crisis period. The market has much less capacity than it used to have,” William Perraudin, director of Risk Control Limited, said.