A low-yield environment is here to stay. The US Federal Reserve looks likely to keep short-term interest rates near zero for five years or possibly more. This brings upon certain challenges for investors looking for higher fixed-income yields. Use Overbond’s Similar Bond Screening feature to identify the highest-yielding bonds with optimal liquidity profiles.

Source: Bloomberg

The Federal Reserve looks likely to keep short-term interest rates near zero for five years or possibly more after it adopts a new strategy for carrying out monetary policy.

The new approach, which could be unveiled as soon as next month, is likely to result in policy makers taking a more relaxed view toward inflation, even to the point of welcoming a modest, temporary rise above their 2% target to make up for past shortfalls.

Fed Chairman Jerome Powell is slated to provide an update on the Fed’s 1-1/2-year-old framework review of its policies and practices when he speaks on Thursday to the central bank’s Jackson Hole conference, being held virtually this year because of the coronavirus pandemic.

“I wouldn’t be surprised if interest rates are still zero five years from now,” said Jason Furman, a former chief White House economist and now Harvard University professor.

That would be good news for some investors. Thanks in no small part to the Fed’s ultra-accommodative monetary policy, the S&P 500 stock-market index is trading at a record high even though the U.S. economy has yet to recover much of the ground it lost in the deepest downturn since the Great Depression as the pandemic took hold.

FOMC Forecasts

At their June meeting, all 17 Fed policy makers projected that the federal funds rate they target would remain near zero this year and next. And all but two saw rates staying at that level in 2022. Officials will provide updated quarterly forecasts at their meeting next month, including for the first time projections for 2023.

“We’re not even thinking about thinking about raising rates,” Powell told reporters following the June meeting, in a memorable maxim that he’s repeated since.

Eurodollar futures aren’t currently pricing any premium for Fed rate hikes until early 2023, with a full quarter-point increase priced in toward the end of 2023. Some traders, though, have viewed this as slightly too dovish, with demand emerging for hedges against a steeper path than is currently priced in for 2023 and 2024. Some see ultra-easy monetary policy eventually spurring inflation.

In a sign of economic resilience, government data on Wednesday showed U.S. orders for durable goods rose in July by more than double estimates amid a continued surge in automobile demand, indicating factories will help support the rebound in coming months.

The Fed held rates near zero for seven years during and after the financial crisis before raising them in December 2015. Former Fed Vice Chairman Alan Blinder doubts it will be that long this time, though he adds that he would have said the same thing when the Fed first cut rates effectively to zero in December 2008.

“It’s perfectly conceivable it could take seven years” before rates are increased, given how difficult it’s been for the Fed to generate faster inflation, said former U.S. central bank official Roberto Perli, who is now a partner at Cornerstone Macro LLC.

In the last decade, it took more than three years for inflation-adjusted gross domestic product to rise back to the level that prevailed before the 2007-09 financial crisis. The recovery is expected to be faster this time: Deutsche Bank global head of economic research Peter Hooper sees GDP attaining its first-quarter level in the first half of 2022, though much will depend on the development and dissemination of a vaccine.

Framework Review

But staying the Fed’s hand will be a change in how it reacts to developments in the economy as a result of the framework review.

When it raised interest rates in December 2015, core inflation was clocked at 1.5% — it’s since been revised lower — while unemployment stood at 5%.

Economists said it’s hard to see the Fed increasing rates under similar conditions now.

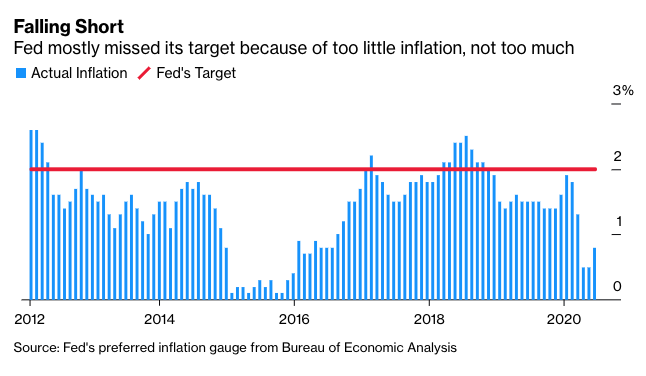

The Fed first pronounced a 2% target for inflation in 2012, and officials took that to mean they would always shoot for 2%, no matter how much or for how long they missed. Bygones, they said, would be bygones. The trouble was that inflation has consistently run below their objective since then.

Under the new regime, the Fed is expected to seek an inflation rate that roughly averages 2% over time. So a modest rise in inflation above target would be welcomed, not feared, after an extended period where it undershot.

The Fed is also expected to codify a change in its approach toward achieving full employment. In the past, officials shied away from pushing joblessness below what was considered its long-run natural rate out of concern that would lead to too rapid inflation.

Now, the emphasis is on the benefits of a strong labor market for the economy and society. “They’re not going to act to cool off the labor market unless it’s generating unwanted inflation,” said Nomura Chief U.S. Economist Lewis Alexander. “That’s essentially walking away from the concept that there is a natural rate that it is irresponsible to push beyond.”

Powell has said he’d like to see the jobs market return to its pre-Covid-19 state, when unemployment stood at a half-century low of 3.5%. It’s now 10.2%.

Blinder said it will take years to do that. “I hope it won’t be decades,” the Princeton University professor added.

The bottom line for policy: a prolonged period of rock-bottom interest rates.

“I’d be very surprised if it’s less than three years,” said David Wilcox, a former Fed official now with the Peterson Institute for International Economics. “I could see it being as much as six or seven years if the damage from the crisis proves to be much more long lasting.”